As the Bo’ness silent film festival enters its fourth year, the five-day programme promises to deliver classics from the silent cinema era, including the unambiguously titled double bill, Before Grierson Met Cavalcanti on Sunday the 16th March. Showing first is Brazilian director Alberto Cavalcanti’s Nothing But Time/ Rien Que Les Heures (1926), an experimental film portraying a day in Parisian life. Following that is John Grierson’s groundbreaking documentary Drifters (1929), which depicts the epic journey of herring fishermen. It was first shown in London in the winter of 1929 to critical acclaim and mass audience approval.

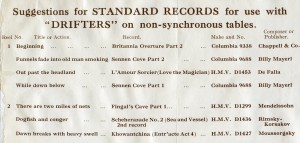

Drifters, not only documents but also dramatises the struggle between man and nature, both poetically and cinematically. Much thought went into the musical score for its original screening and has been updated for the 21st century. The musical accompaniment to Drifters will be Jason Singh, a human beatbox.

At the time of release and for years after, the filmic technique of Drifters has been compared with the Russian school of filmmaking of the 1920s in particular Sergei Eisenstein’s ‘montage’ theory and practice. Eisenstein suggested that the purpose of film editing was to create drama and conflict within the narrative, while creating symbolic meaning through the relationship between shots by means of juxtaposition. In essence, editing consists of several individually filmed shots, that when put together produce a coherent story, thus creating a ‘montage’ or sequence. When the individual shots, such as action/reaction shots, POV (point of view) shots and cutaways (general views) are edited together, a dialectic or conflicting element can arise through these opposing images on screen. In the case of Eisenstein’s films such as, Strike (1924) and Battleship Potemkin (1925) this provoked an immediate reaction from the audience as they grappled to make sense of the visually generated narrative truth. By interpreting the film subjectively the viewing subject was offered a rich cinematic experience. Over time symbolist editing techniques were used by Eisenstein and other directors as a propaganda tool for Russia.

It was Battleship Potemkin that influenced Grierson’s own nascent editing techniques. Film critics and reviewers supported the use of Grierson’s editing style, articulating a new intelligence found in filmmaking and the way films were being read.

“It is really in it’s editing, it’s ‘montage’, that ‘Drifters’ begins to live,” wrote Henry Dobb from the Sunday Worker on 3rd November 1929. (ref. Grierson Archive, G2.24.1)

‘HT’ writes in The British Film Weekly,

“[…] His beautifully chosen angles, the cleverness of his cutting, the beauty of his editing, created a dramatic and thrilling picture.” (ref. Grierson Archive, G2.24.2)

Drifters, was a success for the socially conscious Grierson and in terms of film form and language he adapted to the new techniques, and to the introduction of sound to accommodate his didactic and creative nature. John Grierson went on to produce a plethora of innovative and artistic films, developing over the years to establish his own pedagogical approach to Britain’s social problems, through government-funded films.

(Susannah Ramsay, M Litt. in Film Studies)