In this post, guest writer Bernadette Cahill describes her research into her own family history as it took her from archive to archive. Bernadette is a University of Glasgow alumna and historian, whose research focuses on women’s rights and the suffrage movement in the UK. This blog was originally posted on the University of Glasgow Library blog and is reproduced here by the kind permission of the author.

When I began hunting for more information on a story my mother told me in 1968 – the 50th Anniversary of the Votes for Women victory – I slammed headlong into the Clydebank Blitz.

Mum’s story was about helping to campaign for women’s rights when a student at Glasgow – summer work she had found in Rothesay. As Margaret McCann, she graduated M.A. in 1931.

The Clydebank Blitz of March 1941 killed and injured hundreds and destroyed the densely populated town where 50,000-plus souls had lived. Clydebank proportionately lost more lives than all other blitzed towns and was the only one evacuated. Immense psychological damage was wrought on those who lived the onslaught, which they imparted to later children. And the total damage of homes and contents also caused the wholesale demolition of the foundation of family history through the instant destruction of photos, documents, letters and other personalia.

The Clydebank Blitz hit Mum, her parents, and siblings hard. They all survived, but the home did not, and no usual historical sources survived from before March 13, 1941. There is nothing to show what Mum looked like as a girl; nothing of her with her Mum, Dad, or siblings; nothing documenting the achievements of her early life. No souvenirs from Rothesay offering detail about her story of what she called the Clyde Coast Campaign.

Luckily, I had somewhere to start: a recording of her telling me about the campaign, which I had made with a professional recorder specially bought for the purpose, during a quick trip home from Canada in 1984. By then, Mum was in her seventies and I was aware that time was running out.

The recording told how Mum worked with a Lilian Lenton and others in Rothesay, how Dr. Frances Melville, Mistress of Queen Margaret College had arranged the job for her. How she was taught to attract listeners from the holiday crowds by standing high on a chest and calling, “We are here today under the auspices of the Women’s Freedom League”; how “Madam Lenton,” as Mum called her, taught her how to deal with hecklers; and how wonderful the food was.

But there were no dates. As Mum said on tape, by 1984 there was a lot she could not remember, adding wistfully, “No one nowadays knows anything about the Clyde Coast Campaign.”

There was, however, enough information in secondary sources to allow further work on the women Mum named. Through them, Mum linked me to both militant wings of British suffragism – the violent Women’s Social and Political Union and the non-violent Women’s Freedom League. Born in 1891, Lenton had originally joined the WSPU when she turned 21, vowing to burn down a building a week till women won the vote. Later she worked for the Scottish hospitals in Serbia and when the WSPU disbanded on victory, joined the WFL the 1907 breakaway from the WSPU.

Mum also linked me to the earlier suffrage law struggles, for Dr. Melville was one of the protagonists of the famous Scottish case, fought to the House of Lords in 1908 for women graduates’ right to vote. Dr. Melville’s role as an educator also linked me to the education for women movement which had helped to build the case for women’s vote.

I filled much of this in from wide-ranging research based on Mum’s tape. My sister, Dr. Catherine Smith (B.Sc. 1971) later added many details from memories of talks with her, establishing that Mum, when she was a student at Glasgow from 1927, worked for equality in the vote during the last ten years of the campaign after the principle of Votes for Women was won in 1918. She may even have assisted before becoming a student.

When my Southerner husband digitized the tape on Mother’s Day 2006 and I heard her voice for the first time in more than 20 years it was an emotional event. But the questions the recording raised! At this time, I did not even know when exactly she attended Glasgow University.

Meanwhile, Catherine’s husband, Cairns Mason (B.Sc. 1967) was researching family genealogy and had struck a blank with Mum’s dad in 1905. We had no idea if he had only just arrived in Scotland, for he appeared in no earlier records. The primary fact we had was that Grandpa and sons were riveters in John Brown’s Shipyard.

Then in late January 2007, on a sudden trip home, I knew I had to research in Glasgow University Archives. Not only for facts about Mum, but of my Dad, Thomas Peter Cahill (M.A. 1952). And also potentially about my grandfather and uncles, for I had discovered that John Brown’s Shipyard archives were deposited with Glasgow University.

I just dropped in with no appointment, but the archivists nevertheless opened their doors for me and soon they had found and copied the records for Mum and Dad. These were a treasure trove: not just because of the information they held, such as dates and addresses I had not known, but also because of the emotions they awoke in me. I find it amazing that just seeing the written name can so easily trigger a lump in the throat. One of the most important and emotional documents I found was a letter my Dad wrote when applying for entry to Glasgow in 1948.

The John Brown’s archives represented another treasure trove, for the archivists located the apprenticeship papers of my grandfather, William McCann and those of Uncles Willie and Jim. The most important fact to emerge was that Grandpa signed on in John Brown’s in 1900, which pointed to his immigration from Ireland considerably earlier than the 1905 earliest date we had. With this, my brother-in-law located the 1899 death certificate of my great-grandmother – a sad discovery, because she had died in Stirling District Asylum at Larbert.

All this came to light through my visit to Glasgow University Archives during that quick trip home from the U.S. in 2007. And then the matter largely rested, though I returned fitfully to Mum’s 1968 story. When researching my first suffrage book, “Alice Paul, The National Woman’s Party and the Vote: The First Civil Rights Struggle of the 20th Century,” a huge breakthrough came when the web turned up the WFL newspaper through a news item on Paul. Research there produced the documentary confirmation of Mum’s tale and revealed much further information about the forgotten Clyde Coast Campaign, which seems to have been the longest-running campaign for the vote and equal rights anywhere in Britain.

Then the 2018 centenary of Votes for Women approached, and I found myself planning trips to Britain for presentations in Rothesay, Stirling, Clydebank and Cambridge about Mum’s tale. Meanwhile, a cousin built on the earlier genealogy and the archival work from Glasgow University and introduced from Ancestry.com documents the fact that my great-grandmother gave birth to my grandfather out of wedlock.

How Rose Ann Quinn got pregnant and by whom remains a mystery. But this information led me back one sleepless night to her death certificate, which Cairns found after my Glasgow Archives visit. “What is that?” I demanded of the silence in the dark of the night, looking at the cause of death and jumping onto the web to hunt.

“General paralysis of the insane,” I discovered, was usually linked to syphilis. I was shocked. Who had passed it to her? In what circumstances? Are there records from Stirling District Asylum? It closed many years ago, I found, but – stunningly – then located the archives in Stirling University, a town where I would be speaking in a month’s time.

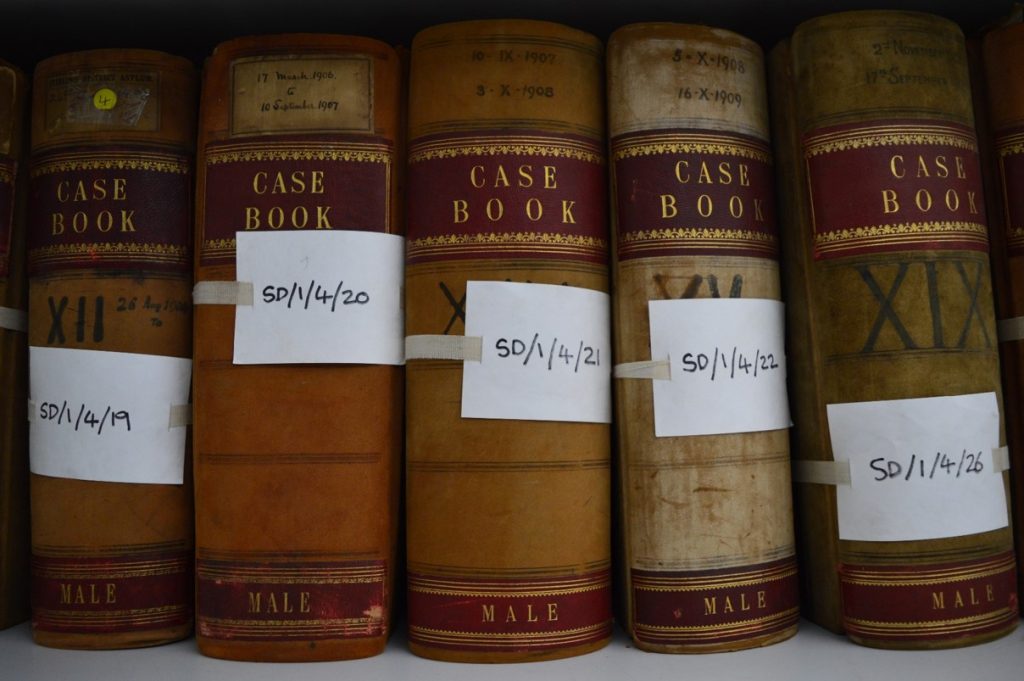

A few emails later, I had a typescript of my great-grandmother’s records and an appointment to see and photograph the originals. On February 9, 2018, the duty archivist welcomed us in, led us to a table with five huge volumes on it, each marked at relevant places. He opened the first one in front of us. And there, on the first page, staring up at me was my great-grandmother’s photo. My husband gasped. I began to cry. The archivist I had emailed had told me nothing of this, and I am so grateful, because it came as such a surprise – a pure gem to find so unexpectedly.

There were many pages to photograph. It was unusual, apparently, to have so much information on one individual in such hospital records – a measure of how serious her condition was. As I was examining it, I found the great-grandchild in me asking, “Granny, why did you have to go through all this hell?” But the historian exclaimed, “Granny, thank you for leaving this trail for us to find.”

Family members’ reactions varied. Medical friends were fascinated. The further implications of my research took some time to sink in. One was that our family now had a photograph of a family member from before that awful night of March 13, 1941, when the Luftwaffe destroyed the McCann family’s home and everything in it. The second was that my great-grandmother’s sad circumstances gave me a direct link to another women’s rights issue – the one women of the 19th century delicately called “the sexual double standard,” which was about venereal disease, brought home to many a wife by her husband.

Another cousin pushed the story further. My great-grandmother later had an out-of-wedlock daughter, married a William McCann, took his name and gave it to her son, William. Was this man the father of her children? Was the father someone else entirely? Does the McCann name correctly belong in our lineage? Who do we come from? The list of so far unanswerable questions is extensive. And this is where the story stands, awaiting a DNA hunt.

The research I began because of my mother’s 1968 story has led to a trail of historical articles and presentations and the Clyde Coast Campaign. The presentation I gave in Rothesay on February 6, 2018, where Mum had worked, attracted a huge crowd and revealed history no locals had heard before.

Librarians, both general and specialized, and archivists, both in the U.K. and the U.S, including the U.K. Parliament and the Library of Congress have given me considerable research help. One stunning experience in the U.S. was the work the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts did to access a letter about Susan B. Anthony – a key document, proving she was not responsible for something she had been accused of in 1867. I found this just as I was reaching the end of writing my book, “No Vote for Women: The Denial of Suffrage in Reconstruction America,” and it led to some re-rewriting. The Radcliffe archivists bent over backwards to send me the best copies possible, despite a major upheaval in their workplace in the summer of 2018.

That was a memorable professional archival experience. But the experience of my encounters with the Glasgow and Stirling University archivists stand out in relief, not just because I met some of the people who dug out the documents, but because the information uncovered with their assistance has partially filled a huge blank in my family’s history. They have also helped partially to heal a forgotten aspect of the long-term damage on people such as my family, Bankies and Clydebank that the Blitz rained down on the town 80 years ago.

Bernadette Cahill’s article, “The Clyde Coast Campaign and Votes for Women in Rothesay 1909-1933,” appears in the 2020 edition of the Transactions of Bute Museum and Natural History Society, Vol 30, pp 8-17.

Bernadette Cahill has written all her professional life for magazines and journals focusing on women’s rights and art. She has spoken in the United States at many venues about women’s rights and written three books about U.S. women’s struggle to win the vote. She has also spoken and written for British outlets about the Clyde Coast Campaign in Scotland, for which her mother worked during the equal and voting rights campaign in the 1920s and early 1930s. Born and educated in Scotland, and having lived also in Ireland, Canada and the U.S., Cahill has also been a programme host on a Northeast Louisiana Public Radio, an artist and a photographer. She is also a licensed Private Pilot and her favourite pastime is ballroom dancing. She lives in Vicksburg, Mississippi. If you wish to contact her about her work, you can email her on historian@reagan.com.