This year, the University of Stirling Art Collection and Archive are excited to host Jennifer Wicks as our artist-in-residence. Jennifer is specifically looking at the work of Normal McLaren. In this blog, Jennifer shares her experience of the beginning of her residency.

So here I am, knee deep in genius. Overwhelmed by the volume of the work McLaren produced and the clarity of his research. The interesting problem to have, is how do I make work from this residency that doesn’t just replicate/ duplicate McLaren, or indeed other artists before me. McLaren pushed his material and technology; he wrote extensively on drawn on film techniques, drawn on sound, stereoscopic art. His technical notes are so incredibly thorough that it almost reads like an engineer. His enthusiasm is not just for the technical, though. His interest is very much around the lived experience, the phenomenology of sound and image and space and the philosophy around perception. These “experiments” however, have definitely not ceased to excite people and humans are always looking to somehow change the inner landscape of their minds.

One thing that has struck me is McLarens need for knowledge exchange: throughout his career he consistently referenced other people; artists who influenced him, artist and musicians who he collaborated with, technicians who helped him achieve his goals. Oskar Fischinger, Helen Biggar, Mary Ellen Bute, Evelyn Lambart, Maurice Blackburn are all frequently mentioned in his papers, correspondence letters, and technical notes. This is one of the many things I’m growing to love about McLaren through my research, his transparency, and his constant desire to learn and advance but, crucially, to share. I think this open and honest sharing was key to his success and made him the “genius” and pioneer of film and synthetic sound that he became. On animated sound on film he said: “The idea is not new. In the early 30’s some Russian technicians and the German Rudolf Pfenniger in his film ‘Tonede Hanschrift’ made experiments along these lines. Currently the Whitney brothers are doing similar research…” This recognition of others is also testament to his thorough research methods that would see him advance technology and creatively explore sound and image and perception through drawing, film, and sound.

In 1980 (a few years prior to his death) he was asked to write something for a retrospective of Oskar Fischinger’s work. He wrote: –

“Around 1936, in my student days at Glasgow School of Art in Scotland, I saw for the first time an ‘abstract’ movie. It was Oscar Fischinger’s film done to Brahm’s Hungarian Dance number five. It’s difficult to describe the impact it had on me. I was thrilled and euphoric by the films kinesthesia, which so potentially portrayed the movement and spirit of the music. The experience had an indelible impression on me, and was a lasting influence on many of my films…. In the early Fifties I had the opportunity and great pleasure of visiting Fischinger and his wife at their home and studio in California…. I discovered that Oscar was not just into film making, but was into all kind of other experiments, the most intriguing of which for me was his stereoscopic paintings, for I myself had been dabbling in binocular drawings”

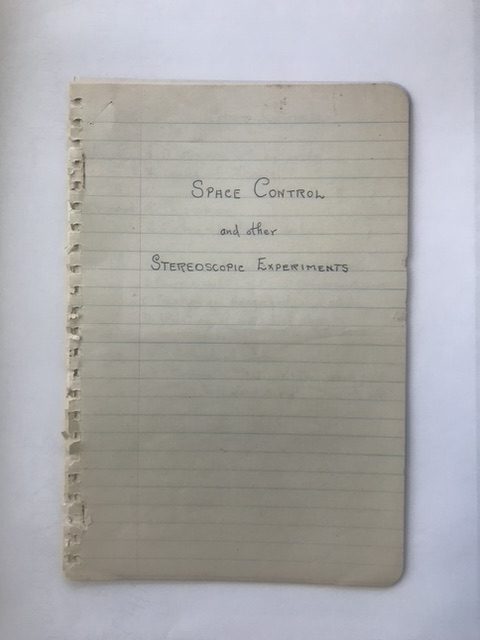

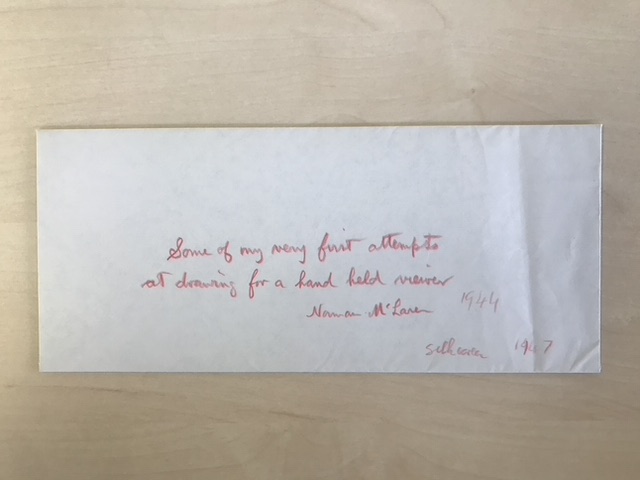

McLaren is well known for his films, but I hadn’t seen any of his stereoscopic drawings until now: single line, some very detailed, some abstract (almost Picasso-like), “the art of doing a separate drawing, painting, sculpture or mobile for each eye, which when viewed together, will synthesize a new additional dimension.” And I think it’s here, stereoscopic drawing, that I’ve found my initial starting point and that will free me up to change my head-scenery to begin making work. As McLaren said, “Freedom from the physical laws of a three-dimensional world.”

And so it begins…..