In this blog Georgia Glass, a final year History and Sociology student at the University of Stirling, writes about the move to online volunteering. With an interest in social and medical history Georgia volunteered on our William Simpsons Asylum project to gain practical experience transcribing 19th century documents.

It has almost been 15 months since the first lockdown was announced in the United Kingdom. In attempts to slow the rise of COVID-19 cases the Prime Minister and First Minister for Scotland had both urged people to work from home. More recently there have been additional lockdowns. The second national lockdown has lasted from the 6th of January and over the last two months a roadmap of the Government’s plans to gradually reopen public services has begun. As a result of this, many of us are still choosing to stay situated a home. Adjusting to the normalization of online learning, education programs have had to incorporate virtual methods, to deliver a wide range of services. Online platforms such as Microsoft Teams and Zoom are concrete in the curriculum. University archives are an example of a department that has had to make changes. While online learning is certainly not new, at this current standstill, it has very much become essential.

University archives in housing different collections, give volunteering students and staff, an opportunity to get a closer “physical” appreciation of the past. In addition, many archives across the UK, have launched contemporary collecting projects, in attempts to document the mechanics of lockdown, including the Scottish Political Archive at the University of Stirling. Other less contemporary projects have developed since last spring, to provide students with a virtual experience.

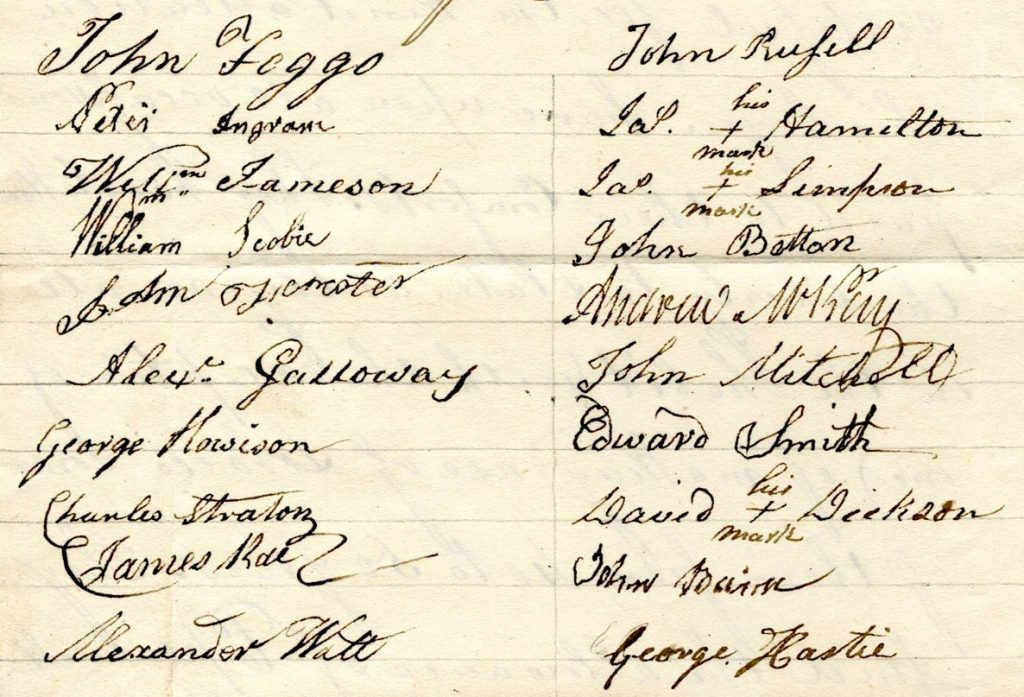

The William Simpson Asylum Project involves the mapping and recording of patient information from the institution that opened in Plean in 1836. Most of the men who were admitted had been in some form of army or naval service and aged between sixty and seventy. From looking at the register notes we find personal information; the length of their military careers, the trades they entered after service and some descriptions of their character within the asylum. Stirling’s access to these documents started in an earlier project in 2018. Students carefully transferred the papers from metal trunks, that had been sitting untouched for 105 years. Fast forward and the project team are currently transcribing a set of papers relating to the first inmates Including a petition signed by 20 inmates, to increase weekly tobacco allowance, and ‘An explanation of misconduct.’ caused by an inmate’s continual snoring.

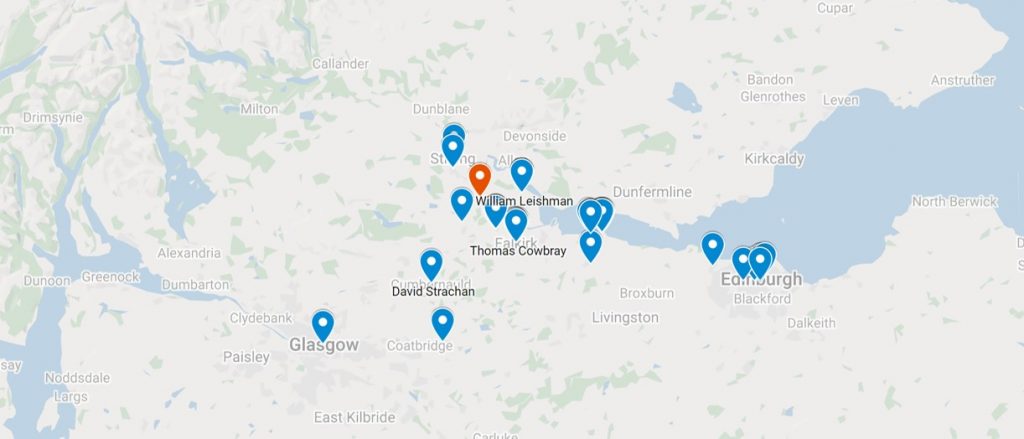

The next step for the project in 2021 is to record details of the first one hundred inmates of the asylum, by using the ‘Descriptive roll of inmates,’ a volume of statistical patient information. In conducting these searches, the archives have made use of the application Google Maps to map out the distance between inmates’ parishes of birth. Furthermore, the project has been working alongside second year history students who have chosen to enroll in a placement module at Stirling. In taking part in this project the students have been able to get experience of working within the archives (in their digitised form) and a taster for paleography in transcribing the Asylum records.

“We hope the move to online volunteering has provided opportunities for students to become engaged with collections during a period when trips to the reading room are not possible.”

Karl Magee, University Archivist

Leanne a former PhD student with an extensive experience of transcribing and one of the volunteers, also notes the pros and cons of the online project. She explains that it is flexible for someone working remotely and offers an opportunity to work with new primary material, noting that “due to the ongoing crisis, it has been impossible to access certain archives and repositories.” The cons, as she notes are that volunteers do not have a chance physically meet, which can be beneficial when editing each other’s work. Secondly “I find it a little hard to contextualize the documents at times because we are not looking at them in person, as you can discern as much about the document from the way it has been stored, found and presented.”

Leanne and Karl have both agreed that the project has been fascinating and have enjoyed putting the inmates’ stories together. As Karl indicates that while the big national online projects are on a much larger scale than Stirling’s, using software like Microsoft Teams allows for the creation of specific projects with the ability to share the material to be worked on.

Presently universities are trying to achieve staggered returns to physical teaching. Though for the Spring semester many students have not been able to engage with teachers in person. It also comes as no surprise that museums and galleries face much uncertainty about their future. Joe Traynor, Head of Programmes and Partnerships at Museum Galleries Scotland expressed last September, that while losing significant income, museums also face anxiety about engaging with returning audiences. As museums are deeply embodied in the community, it has been important to connect with audiences from home.

Georgia Glass, May 2021